Public Art Is Used to Make a Statement About

A giant blue bird sculpture in London's Trafalgar Square challenges our preconceptions most the purpose of public art, argues Alastair Sooke.

"Ladies and gentlemen, here it is: the big, bluish… bird!" And so proclaimed the Mayor of London Boris Johnson last week. On cue, administration tugged at black drapes to reveal the latest public sculpture to occupy the Quaternary Plinth in Trafalgar Foursquare: a gigantic electric-blue cockerel by the German artist Katharina Fritsch.

When I cycled past the sculpture, which is chosen Hahn/Erect, later that morning, it made me express joy out loud. The colour of the rooster, reminiscent of the iridescent, otherworldly pigment patented by the French creative person Yves Klein, offers a surreal, comical contrast to the drab statuary bronze and buttoned-upwards grayness facades of the grand buildings nearby.

More importantly, the double entendre of its title is fully intended: with his stiff, punk-like coxcomb and jowly wattle, this puffed-upward cockerel is meant to appear pompous and ridiculous. I particularly enjoyed his magnificently rumpled tail feathers. In that location's something deliberately deflating about the manner in which they droop, then that the cockerel has the bleary aura of a whoring-and-roistering former rogue, worse the habiliment from potable, still strutting despite being unable to perform in the bedroom.

Here, and then, is a sally by a female artist against the many vainglorious monuments commemorating self-important men that have been erected all over the world. Of course, the rooster isn't the only sculpture of an animal in the vicinity – Edwin Landseer'due south statuary lions at the pes of Nelson'south Column are some of London'southward principal tourist attractions. Nevertheless there are several examples of statues of doughty old heroes in Trafalgar Foursquare – not least Admiral Horatio Nelson, who surveys the British capital from the top of his tall Corinthian column. Fritsch'south work is the latest in a series of temporary sculptures to occupy the otherwise empty Quaternary Plinth in the foursquare'southward northwest corner (the plinth was congenital in 1841 to support an equestrian statue of William 4 for which funds were never raised). It got me thinking about the triumphs and pitfalls of public art.

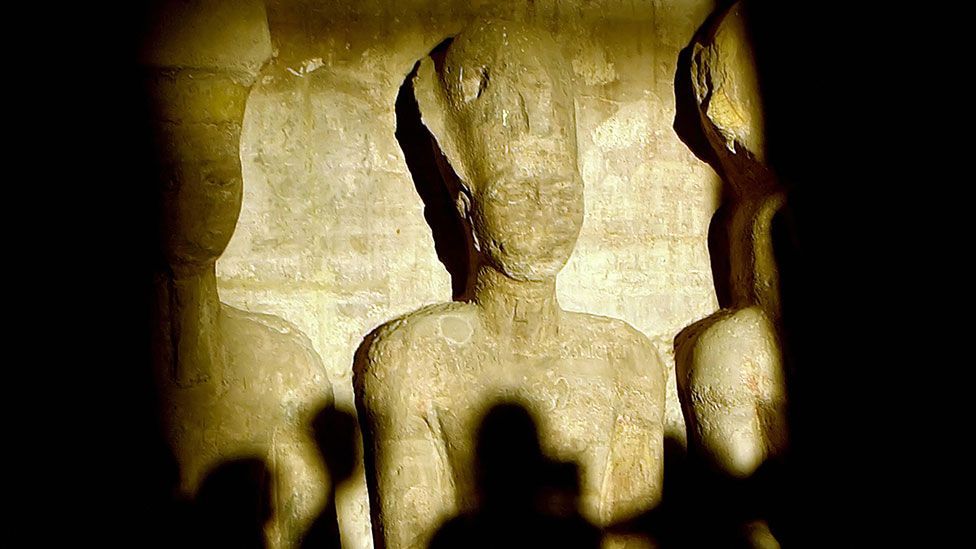

In a broad sense, public art is as former as the hills: remember of the statues of the pharaohs of aboriginal Egypt. The four colossal-seated sculptures of Ramesses II hewn out of the sandstone facade of his rock temple at Abu Simbel in southern Egypt were designed with a very specific public in mind – his Nubian enemies. A edgeless display of royal chest thumping, this is art that bludgeons the viewer into submission. Millennia later, Michelangelo'due south marble statue of David offered another example of the symbiotic human relationship between art and the land: positioned outside in the Piazza della Signoria, it became a public symbol of the independence of the Florentine Republic.

Bronze historic period

In the 20th century, though, public art really came into its own. Conscious that traditional bronze statuary commemorating dignitaries and worthies had go commonplace and overlooked, modern artists vied to produce memorable works of fine art for public spaces. In the decades after World War II, the British artist Henry Moore became the go-to man for prestigious public commissions, and today his distinctive bronze figures and abstract forms can exist seen all over the world.

But today public art is a curious phenomenon. It is big business – the manufacture is thought to be worth tens of millions of pounds each year in England alone – but often information technology exists in limbo, pleasing neither art critics nor the public.

There are many examples of bright contemporary public art that were non allowed to flourish. The American sculptor Richard Serra's Tilted Arc, a 120ft-long (37m) wall of slanting, weathered steel bisecting the Federal Plaza in New York, was synthetic in 1981 but removed 8 years later, post-obit much public gnashing of teeth that so much money had been spent on a "rusted metallic wall". Serra's critic-friendly sculpture did non chime with the public – though his unsettling Fulcrum (1987), which consists of massive sheets of steel propped together similar a potentially lethal firm of cards, is still standing near Liverpool Street station in London.

Meanwhile Rachel Whiteread's concrete sculpture House, a cast of the interior of a demolished Victorian terraced townhouse, was one of the most important British works of art of the '90s. Erected in the fall of 1993, it haunted east London like a ghost until it was removed the following year, in role because locals deemed information technology an eyesore.

Adult female in white

At the other extreme, a lot of public fine art gets commissioned that is popular despite beingness accounted execrable by the critics. After information technology appeared in Chicago, where it quickly became a hit with tourists, Seward Johnson's kitsch statue of Marilyn Monroe grappling with her white dress equally a blast of air blows information technology upwards (a tribute to the actress's famous scene in the 1955 movie The Seven Yr Crawling) featured in a much-publicised list of the worst public art in the world. Depending on your opinion, it now adorns or blights Palm Springs, California.

When public art works, though, it pleases both camps – the aristocracy besides as anybody else. Antony Gormley's Angel of the North in Gateshead, England is a skilful example: a memorial for Britain'southward failing industrial heritage, information technology has go a pop symbol for the country as a whole, starring in trails for the BBC's flagship television channel in the Great britain.

Perhaps the best instance, though, is Anish Kapoor's Cloud Gate, aka 'The Bean', in Chicago's Millennium Park. Like some extraterrestrial visitation, this stainless-steel sculpture resembles a massive blob of liquid mercury. Its distorting reflective surfaces warp the advent of reality and practise strange things to our perception of space. It also provides the perfect backdrop for a killer photograph opportunity.

Fritsch's Hahn/Cock isn't in the same league as Cloud Gate – its jokey, ribald subtext ensures that it feels more imperceptible than Kapoor's archetype, timeless form. But information technology does play clever games with the historical expectations of public art, which and so often privileges men by putting them on plinths.. Good public art doesn't accept to commemorate men – and it doesn't have to be large.

Alastair Sooke is art critic of The Daily Telegraph.

If y'all would like to comment on this story or annihilation else you have seen on BBC Civilisation, head over to our Facebook folio or message us on Twitter.

A giant bright-bluish cockerel was unveiled last week every bit the new sculpture to stand on Trafalgar Square'southward Quaternary Plinth in cardinal London. (EPA/Andy Rain)

Sculptor Katharina Fritsch says humour is a big part of her work – jokingly undermining the vainglorious sculptures of men in Trafalgar Foursquare is all part of the fun. (PA Photos)

Trafalgar Square was created to honour Nelson's naval victory over France in 1805. The admiral might not corroborate of his new neighbour (and its Gallic symbolism). (Getty Images)

Public art has been effectually for years – Rameses the Great was the most celebrated Egyptian pharaoh, with four giant sculptures of him in the temple at Abu Simbel. (Getty Images)

Standing outside the Piazza della Signoria, Michaelangelo'southward statue of David symbolised the civil liberties the Florentine Republic stood for. (Thinkstock)

In the 20th Century, Henry Moore's abstract bronze sculptures were popular for prized public commissions . They tin now exist seen all over the world. (Getty Images)

Richard Serra'due south weathered steel Tilted Arc (1981) divided Federal Plaza in New York – and popular stance – until it was removed eight years later. (Getty Images)

Seward Johnson's giant Forever Marilyn sculpture now stands in Palm Springs later it was moved from Chicago. (Getty Images)

Antony Gormley'southward steel Angel of the N sculpture in Gateshead, England is an case of a piece of work which has both critical and popular approval. (Getty Images)

Anish Kapoor's Cloud Gate, aka The Bean stands in Chicago's Millennium Park where information technology is both a brilliant visual spectacle and a tourist attraction. (Getty Images)

Source: https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20130731-public-art-what-is-it-for

0 Response to "Public Art Is Used to Make a Statement About"

Post a Comment